In the late 1990s

and early 2000s the world began to wake up to the reality of "blood

diamonds," or diamonds mined in regions of sub-Saharan Africa used to

fund violent conflicts, especially in Liberia, Angola and Sierra Leone.

But over the last

decade, activists, scientists, and politicians have also been made

increasingly aware of the use of coltan mining to fund similar conflicts

central Africa, especially in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

In 2009, German

mineral authorities said that Africa produced half of the world's

coltan, significantly up from previous years as major mines in Canada

and Australia were shut down due to coltan's falling price. The metallic

ore contains tantalum, a key element in the production of

semi-conductors and capacitors found in nearly every consumer electronic

device, including iPods, mobile phones and video game consoles.

A study released in

May by the London-based Resource Consulting Services (RCS) said that in

2009, a group of Hutu rebels in Rwanda, the Democratic Forces for the

Liberation of Rwanda, were 75 percent funded by the sale of minerals

like coltan.

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift: The Masisi region in eastern Congo contain important deposit of coltan

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift: The Masisi region in eastern Congo contain important deposit of coltan

But governments

worldwide are starting to take action. US President Barack Obama

recently signed into law a provision requiring more transparency in the

mineral mining sector. The European Union does not currently have any

similar provisions.

The American law will

require companies sourcing coltan from the DRC and its nine neighboring

countries, including Rwanda, to prove that their mineral exports are

conflict-free. Some development activists have said that while this is a

positive development, turning the new law into an effective embargo may

be a nearly impossible task.

But in recent years,

German scientists have said that they have found a method of chemical

analysis to determine which coltan samples are conflict-free. They said

each coltan sample from a particular mine has a given "fingerprint," or

unique set of characteristics.

'It's a totally different mineralogy'

From his office at the

Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources in Hannover,

Frank Melcher has a collection of rock cuttings in small see-through

boxes and plastic bags spread out. Next to each box and bag he puts a

color print-out of pictures taken with an electron microscope. To the

untrained eye they look like pictures of mosaic floor, but for Melcher

they indicate far more.

"If you compare coltan

samples from different proveniences, it's quite obvious," he said.

"This is a sample from Rwanda, this one's from Australia. The dye

distribution is totally different. It's a totally different mineralogy."

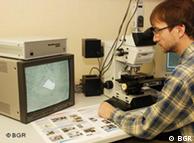

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift: Melcher examines the origin of coltan

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift: Melcher examines the origin of coltan

Melcher is one of many

German scientists working to set up a "certified trading chain," which

would establish the origin of coltan samples.

He relies on more than

using visual cues to identify a coltan sample's provenance. Melcher and

his colleagues also use an electron microprobe that hits the sample

with an electron beam. The emerging x-rays indicate which chemical

elements are contained in the sample.

"I can see right away

what elements are contained in this sample and how much of them," he

said. "Here it's tantalum, there it's niobium, manganese, iron and I

spot some titanium as well."

German government

scientists are using this technique to register the fingerprints of

legitimate mines that then could be compared to field samples mined in

the future. The idea would be to provide incontrovertible evidence

showing that a sample of coltan was mined in a conflict-free zone.

Melcher said he has reference samples from 75 percent of the world's

coltan mines.

"We hope that one day only truly clean products leave African soil," he said.

"In connection with

environmental and social standards this could be the way to go for raw

materials," he added. "We want a trading chain with European and

American companies purchasing goods directly from the African market.

This is impossible for them at the moment."

However, samples from mines in China and the DRC comprise the remaining 25 percent, he added.

"The Chinese aren't interested in delivering samples, and DRC is impossible to access," he said.

European refineries stand to benefit

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift: The German process could limit coltan mining to conflict-free regions

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift: The German process could limit coltan mining to conflict-free regions

Some German companies

have already been affected by the shadiness of the coltan trade. H.C.

Starck, based in the central German city of Goslar, has one of the many

refineries around Europe that takes coltan ore and refines it into pure

tantalum.

H.C. Starck is one of

the few companies capable of completing the complex process of making

tiny, reliable and heat-resistant capacitors out of tantalum. But 10

years ago the United Nations accused the company of using tantalum from

war-torn regions of Congo and H.C. Starck's reputation suffered

significantly.

After the accusations

became public, the company began cooperating with the United Nations and

re-evaluated its coltan acquisition process. Starck now does not

purchase any tantalum from Africa.

"While working through

everything together with the UN panel, we found out, that not every

retailer had told us the truth concerning the material's origin -

despite assuring otherwise," said Manfred Buetefisch, a company

spokesperson. "That's when we realized that - seeing the ongoing war in

East Africa and the DRC - that they are not reliable partners for us,

and that we cannot buy any material there anymore."

Companies like H.C.

Stark are now banking on being able to rely more and more on African

coltan. The company already bought a NRD Rwanda, a small mining company

in Rwanda. Soon, every one of its deliveries will be certified by the

Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources in Hannover.

Rock cuttings for the

license have already been already charted and included in Frank

Melcher's database. By taking random control samples the geologist can

now verify whether coltan was taken from the company's mine in Rwanda.

"This is of course an

ideal case: a company investing in the local mining industry, importing

the coltan on its own and making sure that it is no illegally mined

material infecting the trading chain," Melcher said.

Certification is slow moving

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift: Coltan is often separated from other rocks by hand

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift: Coltan is often separated from other rocks by hand

One year ago the

Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources invited all 10

Rwandan mining companies for a certification workshop. The companies'

chief executives were reserved in the beginning but four companies

joined NRD Rwanda and have signed up for the testing procedures.

Industry analysts have

said that the new practice may pressure African coltan-exporting

countries to clean up their mining practices on their own, without

relying on harsher external policies.

"This might limit

corruption, violence and other conflicts fought over coltan and other

resources," said Peter Eigen of the NGO Transparency International.

"Once the companies voluntarily agree to cooperate, it's easier to make a

point rather than trying to boycott these raw materials or subject them

to certain conditions."

But first, the

Hannover geologists have to adapt their methods to the industry in the

Congo. And they all know that it's a far cry from the way things work in

Rwanda to the unstable situation in the Democratic Republic of the

Congo.

While German

scientists say getting Congo and China to adopt their methods will be

difficult, they said they are confident their process change coltan

mining in the long term. While they are willing to provide the

fingerprinting system, they say that the certification chain must be

located in Africa to be most effective, and that its implementation

remains a local political issue.

"There will be a big

meeting in Nairobi before the end of the year for certification

procedures," Melcher said. "We hope that fingerprinting will be part of

the measures that they take."

Author: Jan Lublinski / Monika Griebeler / Cyrus Farivar

Editor: Sean Sinico

http://www.dw-world.de/dw/article/0,,5907446,00.html