German data visualization specialists seek iPhone tracking data

A Berlin team is asking iPhone users to donate their tracking data as a

way to make a bigger map of WiFi and mobile phone towers all over the

globe. So far, they have several hundred sets.

Late last

month, Apple responded to the revelation that its iPhone and iPad

products track their users' movements across mobile phone networks and

WiFi networks around the globe.

Two British

researchers had previously described at an April tech conference in

California how this tracking data was being stored in an unencrypted

file on the phone itself. They also wrote a data visualization program

so that any iPhone owner could diagram their data on to an

easy-to-understand map.

In a statement

published to Apple's website, the company said users were "confused"

about what exactly the company was doing with this data, adding that it

had never tracked anyone.

However, in

response to all of this, two German data visualization specialists are

now asking for volunteers to donate their iPhone data as a curious

project, known as Crowdflow.net, to map what these iPhones actually

know. To learn more, Deutsche Welle spoke with one of the project's

founders, Michael Kreil.

Deutsche Welle: What are you trying to do here? What's the ultimate goal?

Michael Kreil: The funny thing is that we don't have any goals.

Because it started somehow with a scientific project. It started first

when I analyzed my own iPhone tracking database. And I made a small heat

map of Germany and all the places I've been to. And someone else on

Twitter posted his database and so I took his data and visualized it too

as a heat map of Germany. Then I had the idea that it would be

interesting to take these two databases - his and mine - and to measure

for example, at which time and which places we've been quite close to

each other.

For example, last summer, we've been just 400 meters, roughly, apart

at a demonstration, and then at a conference, we were 700 meters apart.

Then I had the idea -- what would it look like to combine thousands of

such databases and compare them, and what information is really in

there?

It sounds like that at this stage, it's mostly curiosity more than anything else.

Yes, it's just scientific curiosity more than anything else.

Kreil also contributed to the visualization of Malte Spitz' (picture) mobile dataNow, you worked on the data visualization with German politician Malte Spitz, right? Kreil also contributed to the visualization of Malte Spitz' (picture) mobile dataNow, you worked on the data visualization with German politician Malte Spitz, right?

Correct, yes.

I interviewed Mr. Spitz about this visualization a few weeks ago.

And that was such a great visualization. Is that what you're hoping to

do, the same interface, or are you thinking about doing something

different?

The idea behind data journalism is take the data, look into it, and

try to find new relations and new knowledge, and then publish it. We

don't know if we will publish the data in a web application, in a way

that we did for the data retention from Malte Spitz.

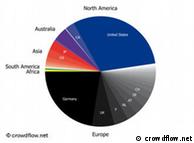

Right now I'm looking at your blog, and it says this is from May

1, and it says ‘First database dump of cell and WiFi stations,' and

there's a darkened map of the globe, and there's a bright spot in

Germany and Europe, and there's a few in the US, and there's some in

South Asia and one in Australia. What's been the distribution of data

that you have so far?

Currently we have roughly 700 iPhone logs, and they're still growing.

We hope that we collect more - perhaps thousands of such log files. And

currently we have a lot of data from Germany, as this project started

here, and we have a lot from Berlin. But the database is still growing

and hopefully we will cover a lot of cell stations and WiFi stations in

America and in other countries in Europe. And we also have a lot of data

from Australia and Japan, and even India. We'll see.

It sounds like you don't even know where this data visualization

project is going. Is that how a lot of data visualization projects go,

that you learn something through the process?

Crowdflow.net aims to reach the entire globeWhen

you combine a lot of data, you never know what kind of information is

in data. Maybe you have one data set, which has a lot of information

[but you don't know what it is], and you have a second data, also with

no information, but at that point where you combine them, you can see

what kind of information and correlations are there. That's the

scientific part. The journalistic part is to combine and look and see if

there is any knowledge or information there. Crowdflow.net aims to reach the entire globeWhen

you combine a lot of data, you never know what kind of information is

in data. Maybe you have one data set, which has a lot of information

[but you don't know what it is], and you have a second data, also with

no information, but at that point where you combine them, you can see

what kind of information and correlations are there. That's the

scientific part. The journalistic part is to combine and look and see if

there is any knowledge or information there.

You can't say that ‘we want to prove that the mobile coverage is

bad,' or that ‘Apple is tracking us.' You can't prove that because you

don't know what's in there. You have to collect it, dig through it, and

then you can see what's there.

So, in other words the story emerges from the data, and not the other way around?

Yep, definitely.

Now if I send you my data, is there any way to tell that this data came specifically from me, and specifically from my iPhone?

The correct answer is, I don't know. For example, [a few years ago]

AOL released a bunch of data about search engines, and [it was later

shown] that they could be de-anonymized. And [later] there was another

example - Netflix.

They matched the Netflix database with the IMDB database. Then they

can see that these people liked these movies and hated these movies. And

then there's also accounts on IMDB with the same profile, so probably

these people are the same. So they use the IMDB data to de-anonymize the

Netflix data.

For now, the US and Germany are the biggest sources of this iPhone dataThere's no way of telling if it's possible to use the track data to de-anonymize these people. I'm not sure, we don't know. For now, the US and Germany are the biggest sources of this iPhone dataThere's no way of telling if it's possible to use the track data to de-anonymize these people. I'm not sure, we don't know.

We started off that everybody can add their name to their log files.

For example when we make a social visualization, that we can make some

kind of a social structure. Currently we are saying that you can say

that you're sending us the data anonymously, but we can't ensure your

anonymity.

In other words, it sounds like what you're saying is that you're not sure if it can be fully de-anonymized or not.

We can't guarantee that it won't be de-anonymized.

But if I send you my file right now, is there any obvious way to know that it came from me, specifically, Cyrus Farivar?

We are deleting our logs and we're not tracking IP addresses and

stuff. But you never know. Sony was hacked twice. If someone is hacking

us and all this data is released, I just don't know. I try to make clear

that we do all we can do to ensure anonymity.

Interview: Cyrus Farivar

Editor: Sarah Steffen data visualization

http://www.dw-world.de/dw/article/0,,15062976,00.html

|